Couch Smut is one fungus that has strong economic importance to the most widely planted warm season grass – Green Couch. Katie Fisher examines the findings from a newly released project on Couch Smut and how OZTUFF and Stadium Sports Couch are both showing resistance to the disease.

The primary cost of Couch Smut to growers is wastage during harvest due to the roll or slab of turf breaking at points of infection. Badly affected turf should also not be sold as a premium product, as both the performance and appearance of the turf is compromised.

But the good news is that certain Couch cultivars seem to be resistant to Couch Smut and have shown no disease symptoms, according to a theory proposed by a research team based in Brisbane.

Above: A/Prof Andrew Geering and Dr Nga Tran inspect the cricket oval at The University of Queensland.

And, within these cultivars are TurfBreed’s OZTUFF and Stadium Sports Couch.

The information was unveiled following the release of a Scientific Literature Review project evaluating the current knowledge and understanding of Couch Smut’s biology which has put scientists (and growers) one step closer to identifying gaps that require future research.

Titled, Couch Smut, an economically important disease of Cynodon dactylon in Australia, it is the work of The University of Queensland – researcher A/Prof Andrew Geering and his team who partnered with the turf industry through Hort Innovation.

Couch Smut (Ustilago cynoditis) is a type of fungus that infects green Couch grass (Cynodon dactylon), the most widely planted turf in sporting facilities, public parks, back yards and school ovals across Australia.

Green couch grass is used at the Gabba, Suncorp Stadium, the Sydney Cricket Ground and most golf courses.

A/Prof Andrew Geering explained that “… when Couch Smut infects Green Couch, it makes the turf bumpy, slow growing and also raises health concerns due to the clouds of allergenic spores”.

“Most people now associate the word ‘Smut’ with crudity, but it is actually an old Teutonic word for ‘black mark, stain’, which in the medieval ages seemed an appropriate term to describe a plant disease characterised by messy black spores,” he explained.

“Although Couch Smut is very common in Australia, no-one’s really looked at how it spreads or how to effectively control it.”

The UQ team are looking at whether Couch Smut is spread by mowing, whether it can be controlled with fungicides, and whether some hybrid cultivars of Couch are immune to the disease.

A/Prof Geering said Couch’s hard-wearing qualities, salt resistance, and ability to be cut very short made Couch a popular choice for sporting facilities, public parks, back yards and school ovals.

He said the disease posed a major headache to greenkeepers, councils, schools and homeowners because it affected the Couch’s playing quality and posed a health risk, but little is known about controlling it.

It appears, however, that both OZTUFF and Stadium Sports are resistant due to their sterile characteristics (see breakout box for further explanation).

“The fungus replaces the seeds in the seed head with a ball of black spores. In badly smutted fields anyone who falls in the grass becomes covered in spores which can cause a respiratory reaction,” A/Prof Geerin explained.

It appears, however, that both OZTUFF and Stadium Sports are resistant due to their sterile characteristics.

“Smut also affects plant growth causing it to grow more upright so you don’t get a nice smooth surface.

“It also weakens the root system, which slows the grass’s growth rate and makes it less resilient to trampling – a key characteristic of Couch.”

A/Prof Geering said the best way to prevent the problem was to buy Certified or Resistant Turf, but once the disease did sneak in there was no effective control.

“The fungal spores are produced in enormous quantities and can travel hundreds of kilometres in the wind, and it’s hard to tell whether the grass is infected until you see the black flower heads,” he said.

Infected grass can be taken out by spot-spraying with herbicide and there have been cases where entire sports fields have had to be re-turfed.

“We’re looking at the management practices of smut in the wheat and sugar-cane industries, where fungicides are used, and where disease-resistant hybrids have been identified,” he said.

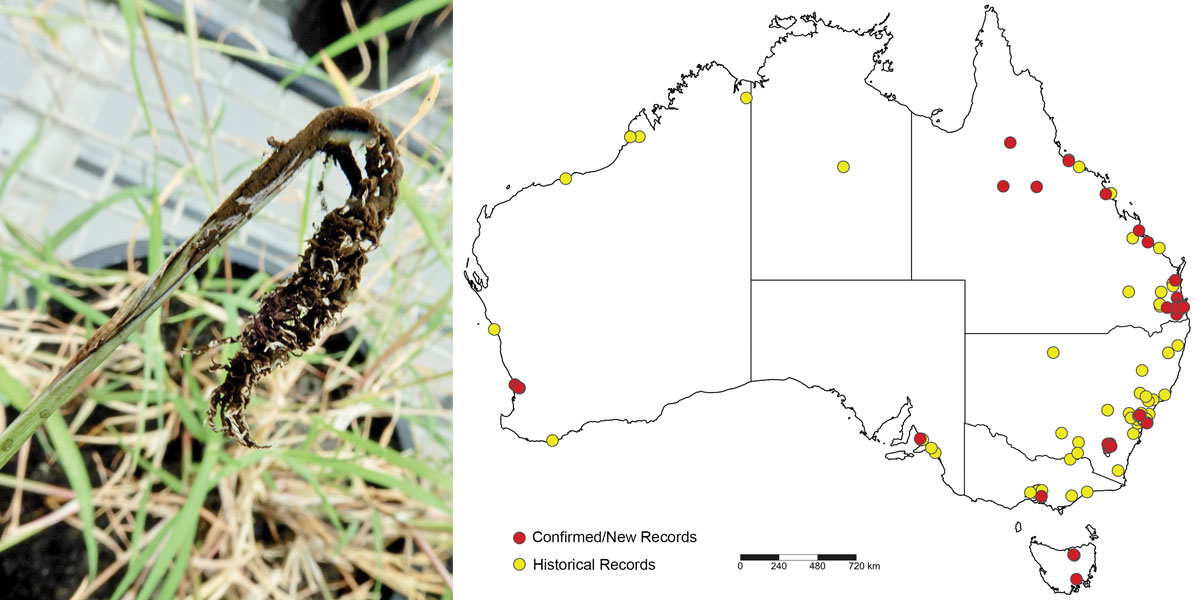

Fig. 1 Distribution of Ustilago cynodontis in Australia.

Yellow dots denote historical records extracted from the Australian Plant Disease Database and red dots denote recent records (2018–19) by the authors of Couch Smut, an economically important disease of Cynodon dactylon in Australia .

What has been learnt about the biology of Couch Smut?

Couch Smut is a very significant and old problem for the turf industry. While other diseases that affect Green Couch (Cynodon dactylon) such as Dollar Spot can be easily controlled through management practices, Couch Smut (Ustilago cynodontis) is a more persistent disease with few management options available.

Project work by scientists at The University of Queensland (QLD), led by researcher A/Prof Andrew Geering and his team, has:

- Reviewed and summarised all current knowledge about the biology of Couch Smut

- Highlighted existing disease management practices

- Presented results of recent Couch Smut surveys

- Evaluated Couch Smut’s impact

- Confirmed the identity of the pathogen

- Offered management/control suggestions

However, the overall conclusion of the project was that to reduce Couch Smut’s disease impacts, an integrated disease management strategy needed to be devised based on sound experimental evidence. Several aspects of the pathogen biology and disease epidemiology remain poorly understood, which hinders future development of a disease management program.

The project’s report states that: “Knowledge of the growth and development of Couch Smut, reproduction, mode of transmission within and between plants, and factors that affect disease symptom expression, will help manage the disease.”

Also, investigating whether current available commercial fungicides are active against Couch Smut will be an important research priority and provide an immediate control option.

Finally, selecting or breeding for resistance to Couch Smut will provide the industry with a sustainable option to manage Couch Smut.

COUCH SMUT – the facts

Couch Smut is distributed across all states and mainland territories of Australia and is found worldwide wherever the host plant is present.

The most characteristic disease symptoms are expressed at the flowering stage, when the inflorescence is partly, or entirely destroyed, and covered by a mass of black powdery spores.

Couch Smut was first found nearly 130 years ago but pathogen biology and disease impacts are still poorly understood, hindering development of management strategies.

Green Couch is a popular variety for home gardens, sporting grounds and in a range of recreational areas, including golf courses, lawn bowls greens, and public parks.

Compared to most other diseases, Couch Smut is more persistent with few management options available.

HOST RANGE

Disease susceptibility amongst a wide range of green Couch cultivars is poorly understood.

The project found that, to date, there had been no methodical disease resistance screening studies.

In the project’s surveys of turf farms in QLD and New South Wales during 2018–19, it observed Couch Smut in tetraploid cultivars of Cynodon dactylon such as Wintergreen, Windsor green and Greenlees Park but no disease was noted in the hybrid, triploid cultivars (such as OZTUFF and Stadium Sports), even when growing adjacent to paddocks of infected plants.

However, the report did state that: “Failure to find the disease does not constitute proof of disease resistance but is an observation warranting further investigation.”

ECONOMIC IMPACT

The economic impacts of Couch Smut are both quantitative and qualitative.

Previous research work in glasshouse trials found infection reduced the rate of stolon extension by 50 per cent and the total plant dry weight (shoots and roots) by 30 – 40 per cent. At high plant density and under conditions of low soil fertility, infected plants also had a smaller root/shoot ratio than competing healthy plants in mixed plantings.

As a result, these impacts on the turf growth reduce the tolerance of trampling, slow the rate of recovery from wear and therefore limit the possible usage of a sportsfield.

It appears, however, that both OZTUFF and Stadium Sports Couch are resistant due to their sterile characteristic.

The weaker root and stolon system of diseased plants also creates problems during harvest; turf growers reported higher levels of wastage during cutting and rolling because the strip of turf was prone to break at points of infection.

Another impact of Couch Smut is when the spores of smut fungi evolve and cause health problems and allergies in some people. The smut spores contaminate shoes and clothing when people walk and lie on diseased turf. Similarly, pets can bring Couch Smut spores into the house on fur.

Smutted turf typically sells at lower prices for commercial applications such as stabilisation of soil at construction sites and on roadsides. To protect both buyers and responsible growers, the Australian Seeds Authority has introduced a vegetative turf certification program, TurfCert™, under which certified turf must be free of Couch Smut.

DISEASE CYCLE

The disease cycle of Couch Smut (Ustilago cynodontis) has not been studied in detail but conclusions have been made from other smut fungi, such as the model organism Mycosarcoma maydis causing boil smut of corn and Ustilago hordei, the cause of covered smut disease of barley and oats.

DISEASE DISPERSAL

As with other smut diseases, the main mode of dispersal of Couch Smut appears to be by wind-borne spores produced in the flower head.

Previous research found that the spores also contaminate seeds, but this mechanism of dispersal would be of minor importance to the turf industry, as commercially cultivated green Couch is multiplied by stolons that regrow over freshly harvested ground. Couch seed is only used when large areas of low value land need to be vegetated, such as roadside verges.

Spores are also thought to be transferred within and between farms by mowers and farming machinery. However, the project reported that this mode of dispersal needs to be experimentally validated.

Fig. 2 Smutted inflorescences of couch grass (Cynodon dactylon) caused by Ustilago cynodontis.

Image A: open inflorescences completely destroyed and covered with masses of powdery smut spores.

Images B and C: open inflorescence partly destroyed.

Image D: infected inflorescence enveloped by leaf sheaths.

DISEASE MANAGEMENT

Management of Couch Smut is challenging because information about disease outcomes is lacking. Currently, the only management tool exercised by turf growers in QLD is removing diseased plants (spot-spraying with herbicides or physical removal by mechanical means such as chipping) or completely replacing diseased paddocks with alternative turfgrass species.

Although removal is a labour-intensive method of disease control, some turf growers have reported that they eliminated or reduced the disease incidence using this method.

Application of fungicides is an important component of integrated disease management of other smut pathogens such as sugarcane smut (Sporisorium scitamineum), loose smut of barley and wheat (U. nuda) and (U. tritici) and head smut of sweet corn.

Chemical compounds that have shown activity against these smut fungi include the triazole group of fungicides, plus azoxystrobin and iprodione, although these have not yet been tested against Couch Smut.

Several fungicides containing these active agents are already registered for control of various turf diseases in Australia and these registrations could potentially be extended to Couch Smut if efficacy were to be demonstrated.

Previous work also found that a modification of cultural practices could help control Couch Smut with glasshouse experiments finding that Couch Smut had a negative effect on the survival of the plant when grown at high densities and/or at low nutrient levels.

Most importantly the project noted that disease resistance is an area of disease management that needs further exploring.

All triploid hybrids (see explanation in Mechanics behind OZTUFF and Stadium Sport’s Couch Smut’s resistance) (for example, OZTUFF, Stadium Sports and Santa Ana) that have been generated by crossing tetraploid C. dactylon with diploid C. transvaalensis (for example, Tifgreen Bermuda grass) are sterile, although these sterile hybrids still produce a seed head and pollen sacs.

It is unlikely that these hybrids carry conventional disease resistance genes, as both parent species are recorded as being hosts of the fungus. Nevertheless, the project firmly believes there is merit in screening a range of genotypes of the pure species to see if there is naturally occurring resistance against Couch Smut.

Further reading: Tran, N.T., McTaggart, A.R., Drenth, A. et al. Couch smut, an economically important disease of Cynodon dactylon in Australia. Australasian Plant Pathol. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13313-020-00680-1

A copy of the scientific review can be obtained by contacting TurfBreed at E: comms@turfbreed.com.au

Couch Smut Resistance!

THE Mechanics behind OZTUFF and Stadium SPORT’s Couch Smut resistance

Want to understand the science behind why TurfBreed’s two Couch varieties appear to exhibit resistant traits to Couch Smut? …read on.

Hybridisation of genetics is behind the resistance of TurfBreed’s two Couch varieties – OZTUFF and Stadium Sports.

Put simply, genetic hybridisation is the process of cross-fertilisation (of two grass species from genetically different populations to produce a hybrid. A genetic hybrid therefore carries two different forms (alleles) of the same gene.

The aim of hybridisation is to produce a hybrid variety that exhibits ‘beneficial traits’ in areas (such as resistance to Couch Smut) which resulted through the combination of these ‘beneficial traits’ from both parent grasses.

Now here the science goes into more detail – most Common Couch’s (Cynodon dactylon) are what we call tetraploids and are known to be genetically unstable. They also have the capacity to adopt unwanted developmental traits – such as Couch Smut.

OZTUFF and Stadium Sports (both Cynodon dactylon) are, however, triploid hybrids and therefore sterile as they have an odd number of chromosomes (the genetic make-up of a plant). This type of genetic make-up means a plant is sterile. Such genetics can be useful to plant breeders, for example Kenda Kikuyu cultivation created a sterile triploid grass, which can be propagated asexually and will not contain any seeds (great for allergies).